This month’s issue of the HOMEbound Nature News is brought to you by the Humboldt Marten.

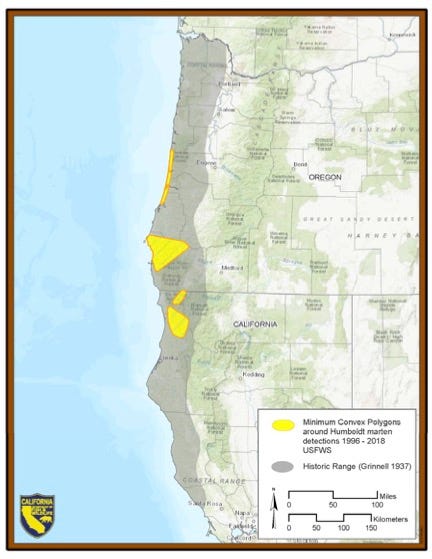

This silky-soft, agile, and fierce little predator lives only in four tiny populations in the forests near the border of Oregon and California in the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Separated by uncrossable artifacts of civilization — highways, clearcuts, and cities — perhaps 400 of these undeniably adorable little hunters survive, total, divided among their isolated patches.

While heartbreaking, this is actually a bit of an improvement. Humboldt martens were thought to have gone extinct in the 1940s (from a combination of fur trapping and the loss of their old-growth homes) until a remnant population was discovered by accident in 1996.1 Wildlife biologists retrieving track-plates set to survey for other Pacific forest carnivores were surprised to discover two tiny tracks that corresponded to the marten’s.

Because they’ve only recently been rediscovered, and their behavior is so elusive, a thorough species description is still a work in progress. Nevertheless, a few things are known.

First, they are more or less old-forest obligate. They refuse to cross clearcut openings, and prefer to hunt within the complex woody castles created by large living and dead trees (called snags when still standing, and logs when they’ve fallen to the forest floor).

Unlike their cousins the pine martens, the Humboldt marten has a strong preference for huge trees, dead or alive, in which to rest and make dens to raise their young. One study found that Humboldt martens used trees and snags averaging one yard (one meter) across for their resting sites, with an average age of 339 years! They chose trees ranging from 131-667 years old; clearly, these are not trees and/or snags that would be found in the sort of short-rotation forestry common in this part of the U.S., where trees are “harvested” every 40 years or so, and the forest “cleaned” of all dead wood. These are the very structures that wildlife need to survive, and their lack is one reason why tree plantations can never be homes for many of our forest creatures.

Second, Humboldt martens are truly wee. While ferocious, they only weigh 1-2 pounds (less than a kg) and are the size of a small housecat. They need only 80 calories a day to survive, but that corresponds to eating almost a third of their body weight daily. They will eat almost any other small animal they can catch, but they are also voracious berry-eaters. Interestingly, research has shown that certain wild berry species’ seeds germinate more readily having first passed through a marten’s digestive system.

Like the marbled murrelet, the forest-and-sea bird that was last issue’s sponsor, the Humboldt marten is so closely tied to its specific habitat that the lines between plant and animal seem almost to blur. In a very real sense, the marten and the murrelet are the ancient forests, each able to survive fully only in the presence of the other. They’re extreme specialists, harmed all together when the encroachment of the generalists — tree plantations, crows, humans — limits the physical space their unique webs of life can occupy.

Marten population dynamics are such that the loss of even two individuals to a human-caused death, such as by trapping or roadkill, is enough to send that population to extirpation by the end of the century. With only four small populations remaining, that’s pretty precarious.

Yet, recent strides have been made. The state of Oregon has banned fur trapping within the martens’ range (California did so 80 years ago). The federal government, as well as the state of California, have extended them Endangered Species Act protections. And as of last month, thanks to a lawsuit brought by the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity and others, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has dedicated critical habitat that, if all goes well, must be preserved for their survival. (Full disclosure: I drafted the legal petition to Oregon wildlife officials advocating for the trapping ban, and my colleagues and I advocated for state and federal Endangered Species Act protections.)

One of the martens’ refuges is located in a rare patch of coastal forest in the Oregon Dunes recreation area, managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Approximately 71 martens eke out a living there, but they are heavily threatened by people driving dune buggies through their habitat. The martens’ unflagging champions at the Center for Biological Diversity filed suit again last month, because the Forest Service is failing to enforce limits on joyriding in the martens’ home. So, progress will eventually be made there, once the court finds in favor of the nonprofit plaintiffs (because they’ve got the law on their side).

Hope is not lost!

Here’s what I was listening to while writing the marten’s profile:

Check out FogChaser’s work here on Substack if you have not already had the chance!

Happenings in the Substack Ecosphere

I gleaned these items from my own travels through the work that’s on offer here by our listed artists.

(And if I highlighted your news below but didn’t get something quite right, please let me know so I can correct it!)

In future, please feel free to submit your news directly to me to be considered for inclusion.

These news items could concern your works published outside of Substack, writing or grant opportunities you’d like to share, online or in-person gatherings — what else? Let me know!

Send items of interest to ourhome@substack.com

A new documentary highlighting the importance of prairie wetlands as North American wildlife habitat is now available on Vimeo. It’s called Fluddles. I’ve watched it, and it’s a delight. It was co-created by Substacker Bill Davison of Easy by Nature; check out his essay on the film and find a link to view it here.

James Roberts of Into the Deep Woods has opened his bookstore and gallery in Wales, described as such on its website:

River Wood is the only gallery-bookshop in the UK dedicated solely to wildlife and wild places. It is situated in Rhayader, the outdoor capital of Wales, close to the famous Elan Valley, a Dark Skies Reserve and a wild landscape of lakes, woods and mountains.

If I make it to the British Isles someday, this’ll be top of mind for a visit. I hope James will forgive me for sharing his photo of the shop below. It’s just so lovely.

Julie Gabrielli has launched the Reciprocity interview series over at her Substack Homecoming. So far, she has interviewed Antonia Malchik, Katharine Beckett Winship, and Jessica Becker, and just when I think the answers cannot possibly get any more thoughtful, she posts another. Head on over and catch up on the series.

Three directory writers have new books available for pre-order.

Field Notes writer Christopher Brown’s new book A Natural History of Empty Lots promises a “genre-bending blend of naturalism, memoir, and social manifesto for rewilding the city, the self, and society.” Hell yes. Available here.

Laura Pashby (Small Stories with Laura Pashby)’s book Chasing Fog sounds like a dream, and I can’t wait to read it. It’ll be a “captivating meditation on fog and mist, a love song to weather and nature's power to transform.” Blackwell’s has it here, with free shipping to much of the globe.

Janisse Ray of Trackless Wild with Janisse Ray and The Rhizosphere (for Writers) recently completed a Kickstarter launch for her new book on the craft of nature writing. So excited for this one. The Kickstarter closed successfully, and the book, Craft & Current, is now available for pre-order here.

Brandon Keim of The Catbird Seat here on Substack recently wrote this fascinating profile of the muskrat over at Hakai Magazine. If you’re not familiar with that publication, its high-quality nature reporting is a consistent bright spot in the science media landscape.

Thomas Winward of Urban Nature Diary has produced a new documentary called The Birdwatchers. Thomas says: “Through the lens of four inspiring women, The Birdwatchers aims to explore and break down some of the barriers preventing people from accessing nature. This film is a love letter to the world of birds, and a rallying cry for people to protect it.” More information is available here.

Finally, welcome conservation journalist Michelle Nijhuis to Substack! Many of us will have read her book Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction and followed her work at publications like High Country News. I look forward to reading her upcoming writing here at Conservation Works.

Gratitude

Let me express here an old growth forest’s worth of thanks to the folks who’ve contributed to the care and feeding of this slightly feral nature writer. Your kindness is overwhelming. Special thanks to those taking out paid subscriptions:

🐾 A cozy marten’s den in a 500-year-old tree to you, Rob Lewis, for supporting this work and for all the work you do on behalf of our Earth at The Climate According to Life. Rob’s work is “weeding through the technical jargon to reveal the glimmering details of how this planet, through living soils, plants and animals of all kinds, upholds and regulates the climates we live in.” He brings such clarity to these complicated issues.

🐌 An unbroken expanse of true silence, the kind that’s filled only with the sounds of nature, to you, Julie Gabrielli, for your firm support of this idea and for your incredible work rallying the nature artists of Substack to raise their voices at Homecoming. I look forward to the evolving journey!

🫐 And the softest shush of a marten’s satin fur as she slinks into the huckleberry patch to you lovely ones who supported all this with a bit of cash to the tip jar:

Bryan Pfeiffer, who publishes Chasing Nature

J. Paul Moore, who publishes J. Paul’s Substack

Glyn Lehmann, who publishes By Nature

Kind reader Deborah Garson

With a full heart, I thank you all.

New Directory Listings

Welcome to the following Substackers, added or updated since our previous issue was published. We are hovering at just about 250 nature-based publications here — I’d say we’re an Earth-loving voice to be reckoned with!

Nature Listening Points by Brenda Uekert (United States)

Mary’s Pocketful of Prose by Mary Hutto Fruchter (United States)

Heather in the Blue Mountains by Heather Dickinson (United States)

The Planet by Alexander Verbeek (World-wide)

Moving Mountains by Louise Kenward (UK-based but world-wide)

still sketching by Deborah Vass (United Kingdom)

Mysteries that Matter by Diana Renn (United States)

Wild and Wonderful by Kate Bown (Australia)

True Nature by Emma Liles (United States)

Earthly Encounters by Jaq Kurio (Europe and UK)

North Florida Nature by Phil Tanny (United States)

The Hidden Pond Substack by Dudley Zopp (United States)

Tides and Seasons by Anna Rose (England)

The Foibles of a Florist by Sarah Rushbrooke (Europe and UK)

The Rising of the Divine Feminine by Camilla Sanderson (United States)

Next Adventure by Jesse McEntee (United States)

By Nature by Glyn Lehmann (Australia)

Psyche’s Nest by Sally Gillespie (Australia)

Spinning Her Wheel by Kelle BanDea (England)

Everywhere is Sacred by Scot Quaranda (United States)

Dear Magician by Rosie Whinray (New Zealand)

Sixburnersue by Susie Middleton (United States)

RainMakers & ChangeMakers by Emily Kaminsky (African continent)

Towards Eudaemonia by Peter Yates (Australia)

~~If you haven’t submitted the form to be listed in our themed and regional subdirectories, you can do so here, for free:

https://forms.gle/JRxZUHqUrhkFDiyY9

🦉 A Gentle Word of Caution for Substack Nature Writers and Artists

I have seen several posts on Substack Notes in the past few weeks describing how writers have chosen to manually unsubscribe any free subscribers who don’t appear to ever open their newsletters. I understand they’re doing this in an effort to boost the “open rates” for their publications.

Then, in preparing this month’s newsletter, I discovered that I was no longer subscribed to several publications of which I have been a consistent reader and longtime subscriber. I don’t know if the authors unsubscribed me, or whether this may represent a glitch on Substack’s end. (I immediately resubscribed.)

Whatever the case, I’d like to gently caution publications against manually unsubscribing their readers who appear inactive, for two reasons:

One, some email providers have put in new privacy measures that prevent senders from knowing whether an email has been opened. Those readers’ “opens” will not be reported by Substack in your publication stats.

Two, an increasing number of readers open publications only in the Substack app or in the Substack inbox on the website. I, for one, do not receive any newsletters in my email; I receive them all via the Substack inbox, and it is unclear whether readers such as myself show up in the publications’ “open rates.”

As far as I can discover, Substack has not provided clear guidance on these metrics and how they are calculated in the two scenarios I mentioned. Until we are certain, I would caution writers against jumping on the bandwagon of “cleaning up your subscriber list.” It’s possible you might accidentally unsubscribe some of your most devoted readers.

If you are still certain you want to cull your subscriber list, I’d suggest you might like to email those folks who appear to be inactive to ask them whether they’re still interested and what they’d prefer you to do.

Okay, public-service announcement over. If I get better information on this at some point, I’ll be sure to pass it along. 💚

P.S. Here’s a wonderful novel; one of the characters is an Oregon marten (not the Humboldt coastal subspecies I wrote about above, but close enough for our purposes). :)

💌 Can you give this community a little compost to help it grow? Send this newsletter to a friend, share on your site, or put a link in Substack Notes or another social media outlet.

🍃 And remember to reach out if you have news to share for next month’s edition of the HOMEbound Nature News: ourhome@substack.com

See you in August, and until then, be well.

💚🌲🦉

The HOMEbound Nature News and HOME | Nature Directory are labo(u)rs of love. It is important to me that these resources remain free in perpetuity. And yet, they represent many long hours of work, so any contributions are received with great gratitude.

You can subscribe for free below, or choose a paid option. Alternatively, feel free to drop a tip of any size in the tip jar! Many thanks.

Recent genetic analysis has confirmed that technically (in U.S. wildlife agency terms), the Humboldt marten is the “coastal distinct population segment (DPS) of Pacific marten” with the complete name Martes caurina humboldtensis.

Wonderful, wonderful issue, Rebecca!

Wonderful. Thank you for the shoutout to Martin Marten, a book which never makes it back to my bookshelf. I need a big fat wrinkle in time to read these publications and books!